What Can We Do About…Tragedies in Other Countries? Anything?

Last week, I introduced blog readers to a woman named Natalie who had lived in the same neighborhood for decades. Yet, somehow after Natalie died, her death went undiscovered for eight years.

I described how stories like Natalie’s keep me awake at night. How it seems like every day, we’re seeing more and more hard-to-read headlines about terrorism, mass shootings, sexual assault. And how these disturbing events always get me rethinking things–how society operates, where connections are breaking down, and how we might do better.

But I’ll level with you. Sharing stories like this gets tricky. Because I inevitably hear from one of our Always Pragmatic Friends.

“It sounds like you think it’s our responsibility to take care of every Tom, Dick, and Harry on the planet,” My dear Always Pragmatic Friends say, “And we all know that is [insert your favorite adjective: impractical/naive/adorably idealistic/laughably out of touch/embarrassingly uninformed].

“Don’t you think it’s a bit unrealistic to suggest we’re responsible for the entire globe? Are you really suggesting we respond to every earthquake, every hurricane, every tsunami? Every coup, famine, human rights violation?”

Granted, my first reaction to these questions is usually to be defensive. (Because how dare you?) But, inevitably, I end up concluding that their commentary is…

Entirely fair.

Sure, it’d be great if we felt some camaraderie with people on the other side of the ocean. If we saw opportunities to humanize them or ease their burdens. But, practically speaking, is that even possible?

I, of course, *just so happen* to think the answer is yes. (As a person who writes manifestos about social connectedness would.)

But I acknowledge the conversation requires some nuance. So here’s a few things I’ve been mulling around related to this. (There’s more to drill down on beyond this of course, but we have to start somewhere, right?)

1. It IS natural for us to be more concerned about our own lives, than other people’s.

But when we click on the story, and we find out it happened in–say–India, we probably let out a micro-sigh of relief.

So, yep. When we read a headline that says 50 people were killed in a subway accident, we might quickly investigate out of concern for any loved ones who commute on the local train. But when we click on the story, and we find out it happened in–say–India, we probably let out a micro-sigh of relief…and often close out the article content to go about our day.

That’s because our default “field of view” is set to our nearest, geographic region. We tend to care most about what happens to ourselves, our family, our house, our neighborhood. As follows, the closer a tragedy strikes to home, the more we care. Thus, if a problem threatens “our people”–the ones like us, who we like and deem valuable–we are more likely to respond.

And this makes sense. Psychologists call this tendency to give preferential treatment to our own group “ingroup bias.” And even though it sounds a little middle-school cliquish, it’s totally normal. It’s likely part of how God hard-wired human beings to band together to ensure the survival of our communities.

2. Since we’re human, and we don’t have infinite resources or bandwidth, we have to be balanced in the way we extend ourselves beyond our immediate community.

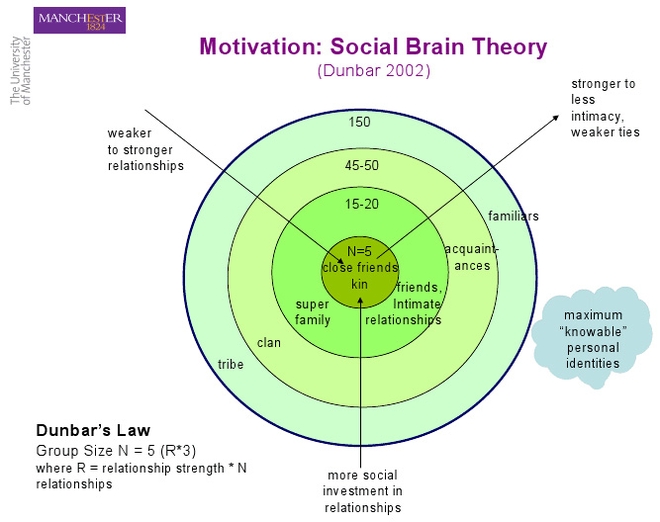

This is where I’d like to introduce you to Oxford professor Robin Dunbar. Dunbar’s work has perhaps contributed more to our understanding of how humans connect than any other living researcher. Among his many undertakings, Dunbar studied a. how many friends people typically have and b. how “closeness” tends to be expressed across people’s friend groups. To get your head around his theory, you can take a look at this chart (above right).

As you can see, Dunbar’s extensive studies found the average person has about 5 “kin” relationships made up of family or incredibly close friends. Beyond that, he discovered we tend to have around 15-20 intimate relationships–the friends and relatives that serve as our “extended family.” Moving further out, Dunbar found we have around 45-50 acquaintances–people in our networks who we could rely on for information or casual conversation but who we might not call “friends.” And lastly, Dunbar said we have a relationship with 100-150 “familiars”–people we recognize as belonging to our groups or community, but who we don’t engage in personal relationship.

When you add up everyone inside these rings of connection, Dunbar concluded that the total number of relationships a person can comfortably manage is between 100-250.

I’d like to throw out a simple extension of Dunbar’s model, as it relates to how we care and respond to the people who share our world.

I would suggest that our level or responsibility to a person depends largely on where they fall inside a diagram like Dunbar’s.

I would suggest that our level or responsibility to a person depends largely on where they fall inside a diagram like Dunbar’s. If the person in need falls under “kin,” for example, we’re highly obligated to try to help them. If they are diagnosed with an illness like cancer, we’re probably the one who brings them to their medical appointments. Who run to the pharmacy to fetch medicine or who bring in a cool towel for their foreheads.

If the person is a “friend-who-is-like-family,” on the other hand, we might not be the most involved supporter in their day to day life. But, we hopefully still offer a high degree of care and service to assist them. Maybe we accompany them to one or two important medical appointments. Perhaps we visit them at the hospital. We volunteer to run errands–to regularly shuttle their kids to games or recitals, to grab them some good books at the library to pass the time.

But what if the person falls outside of those close-knit groups? What if the person is just an acquaintance? In the example of a cancer patient, our response might include sending cards or even flowers to the hospital. Maybe bringing over a casserole, mowing their lawn, or shoveling their snow. Leaving encouraging comments under their Facebook posts. (I know. Who knew Facebook could be used for something other than flaming political memes, right?)

What if the person is even one more layer removed though? What if they’re just a familiar face, a co-worker in another department who you only see in quarterly meetings? Or the parent of one of your children’s friends who frequents the same soccer matches? What does care and response look like then? For the big-hearted among us, it might look like attending a local fundraiser that helps with the family’s medical costs. Standing and clapping for them when they’re acknowledged during Cancer Awareness week. Pausing to ask how they’re doing when you run into them at the grocery store or the school crosswalk.

Here’s where we get to the real heart of our Pragmatic Friends’ question. Because we have to acknowledge that we all have limits. There are even studies, like Dunbar’s, that point to the maximum number of relationships we can comfortably maintain. So once we get beyond those 250 people in our social spheres, do we have any responsibility to outsiders beyond these rings?

So once we get beyond those 250 people in our social spheres, do we have any responsibility to outsiders beyond these rings?

I am willing to concede that we have less responsibility to people outside our community than we have to those inside it.

But that’s not to suggest it’s, therefore, impossible to respond to outsiders.

We don’t want to set up an equation where the only two options are:

A. Dive in and care for strangers’ everyday needs as you would your own sick child.

or

B. Do not care at all and do nothing to respond.

There’s probably a third option, right? For example, let’s imagine a tragedy has struck a community of strangers on the other side of the ocean then. What could a reasonable response look like? At the very least, we could–say–tweet a hashtag of support, right? Maybe share a post on Facebook to raise awareness. We could purchase a product that donates a percentage of profits to their support. Ask a congressman to vote to address their plight. Say a prayer. Text to donate $10.

Now are these perfect or complete responses? No, they are not. In a later post, we could explore how it can be an illusion to think we’re changing much solely by re-tweeting a social media post. But I throw these responses out as practical examples–actions that allow us to extend goodwill and respond to need even when it extends beyond the rings of our local community.

(We’ll talk about how we’re sometimes drawn to go to exceptional lengths for strangers/outsiders in a later post too.)

Listen to my podcast interview with Dr. Robin Dunbar here.

3. When we strive to extend goodwill to the furthermost edges of the earth…it naturally encompasses everyone in the rings between here and there.

If our goal is only to take care of our own, the reach of our compassion will likely end up being small.

If our goal is only to take care of our own, the reach of our compassion will likely end up being small. After all, we naturally tend toward in-grouping; toward exclusivity not inclusivity. This is why I think it makes sense to start with a generous philosophy and work our way toward the practical.

In fact, this is what I think Jesus was suggesting in his popularly referenced parable about the Good Samaritan.

I think Jesus made the main character a Samaritan–a person of a different race than his Jewish followers–for this exact reason. He could’ve just as easily chosen to feature a story where a Jew helped another Jew, right? But if he did that, there’s a good chance his listeners would’ve walked away believing Jesus just asked them to love people of their own race. Because that’s our human default. In-grouping. Inclusivity, not exclusivity.

Instead, though, Jesus started with the more global perspective. Extend yourself toward someone from a different region or race, so much so you love them like you would a neighbor.

If you are ready to love only your geographic neighbor, you won’t likely be prepared to love much of the world. But if you’re ready to love the world, you’ll be well prepared to love your neighbor.

If you are ready to love only your geographic neighbor, you won't likely be prepared to love much of the world. But if you're ready to love the world, you'll be well prepared to love your neighbor. Click To Tweet —So do I think we should respond to every need that crosses our path?

What I think is that compassion shouldn’t have a set, geographic radius.

What I think is that instead of tuning out the suffering of strangers, we should tune in.

What I think is we should seek to gather outsiders to us, rather than divide “them” from “us.”

What I think is we should search for a logical way in, rather than a rational way out.

What I think is, even though we may not have an obligation to help, we still have a choice to help.

What I think is just because you have “the right” to take a pass, doesn’t mean it is right to take a pass.

What I think is it’s better to donate a buck than pass the buck.

What I think is that, at the very least, your prayer can go places where you and I cannot.*

What I think is it’s better to root for others to win, rather than always winning alone.

—

(*That’s a paraphrase of a Brother Andrew quote, in case you’re wondering.)

Ashley February 21, 2018 (3:46 pm)

Yes. Yes. And another resounding yes! Your points almost feel obvious when you spell them out in the way you have but it does not deter from that fact that if we have the ability to act, we should. It may not mean that we choose 50,000 things to get marginally compassionate about but perhaps picking 2-3 that we get intensely compassionate about and start moving in that direction to help. I loved this. Thank you!